Stephen Lesslie

Civil Rights Violation

The Australian disease of insisting that voters must number multiple preferences before their vote will be counted is not an electoral issue. It is a civil rights violation. There is no justification in saying to voters “even though you have made a clear and unequivocal statement with your vote we will not count your vote.”

There is no justification for civil rights violations and this one does not even have the mitigating factor of increasing voter participation.

Fully Optional Preferential Voting

Fully optional preferential voting is not a new concept. The quotes below, separated by almost fifty years, show that it has long been understood that there is no need to require voters to number multiple squares on a ballot paper. Fully optional preferential voting in a single transferable (STV) ballot has been a part of the electoral system in Ireland, Malta, and the Australian Capital Territory for many years without causing the slightest concern.

Enid Lakeman (1903-95)

Director of the Electoral Reform Society (UK)

There is, moreover, no need for the Tasmanian rule that a ballot paper, to be valid, must bear at least three [now five] preferences. The results of the elections could hardly have been different if no voter had gone beyond a second preference, and would have been broadly similar even if everyone had ‘plumped’ for his first preference only. Seeing that only a few voters are likely in fact to behave thus, there would be no justification for interfering with a citizen’s right to indicate that he considers only one candidate to be worth voting for.1

Michael Maley

Associate, Centre for Democratic Institutions, Australian National University

It is sometimes argued that unless voters are required to write more than one ballot paper number, the exhaustion of votes will lead to a situation in which some candidates are elected with less than a quota. It is difficult, however, to see this as a worse outcome than one in which the candidates in question gain a quota on the strength of ballot paper numbers written insincerely and/or at random by voters who have in fact run out of genuine preferences.

With the introduction of OPV below the line, the pragmatic need for the retention of any form of above the line voting as a mechanism for reducing informality would largely fall away. Its abandonment would eliminate preference harvesting, without compromising the ability of small parties to get elected on the strength of genuine preferences of the voters.2

This article will demonstrate that any form of compulsory preferencing in a single transferable vote (STV) ballot reduces the number of voters who are participating in the ballot.

We do this despite believing that it is the responsibility for those who seek to deny voters their franchise to justify their actions.

Voter Participation Rate

Democracy requires that we maximise the voter participation rate. The participation rate will increase if the informal rate is reduced and the participation rate will decrease if the exhaustion rate increases.

The only way to ensure that there are no exhausted votes is to require every voter to number every square. With hundreds (and perhaps in the future many hundreds) of candidates this can only be achieved with undemocratic devices such as above-the-line voting and registered group voting tickets; without these devices the informal vote would soar. As demonstrated in recent Senate elections, the use of these devices is clearly unsatisfactory and must be discarded.

We therefore need to investigate some form of optional preferential voting.

We propose that this form of optional preferential voting be fully optional preferential voting; that is, any vote with the first preference unambiguously indicated should be treated as formal. Voters should be encouraged to continue preferencing candidates but not punished if they choose, for whatever reason, not to do so.

Informal Votes

How many votes, declared informal under more stringent requirements, would be allowed if fully optional preferential voting was implemented?

We believe that being required to vote for as many candidates as there are positions to be filled, as opposed to being permitted to vote for just one candidate, would increase the informal vote in a Senate election by approximately two to three percent.

We base this 2-3% value on a number of observations.

-

Federal Election 2013

Compare the informal vote percentages for the House of Representatives (required to number all candidates) and the Senate (only required a single No. 1 vote). This provides data which compares the effect of two sets of formality requirements on the same set of voters.

|

Informal

|

|

House of Reps

|

5.91%

|

|

Senate

|

2.96%

|

ACT Legislative Assembly 2012 and Tasmania House of Assembly 2010

Compare the informal results for the ACT Legislative Assembly in 2012 (with fully optional preferential voting), with those of the Tasmanian House of Assembly in 2010 (where voters are required to number a minimum of five preferences).

|

Informal

|

|

ACT Electorates

|

|

Brindabella

|

4.0%

|

|

Ginninderra

|

3.7%

|

|

Molonglo

|

2.9%

|

|

Tasmanian Electorates

|

|

Bass

|

4.7%

|

|

Braddon

|

4.8%

|

|

Denison

|

3.8%

|

|

Franklin

|

3.8%

|

|

Lyons

|

4.9%

|

Comparative Lower Houses

|

Informal

|

|

Optional Preferential

|

|

NSW (2011)

|

3.2%

|

|

Qld (2012)

|

2.15%

|

|

Compulsory Marking of Preferences

|

|

Vic (2010)

|

4.96%

|

|

WA (2013)

|

6.0%

|

|

HofR (2013)

|

5.91%

|

Why then do politicians and some sections of the proportional representation movement feel that it is essential that voters in an STV ballot indicate multiple preferences?

Perceived Problem No. 1: Votes might exhaust!

The following are typical comments relating to the perceived problems of exhausted votes.

Comment 1

It is important that voters express multiple preferences when voting. If few voters express multiple preferences there is not enough information for any vote counting system to arrive at a good democratic result. Too many votes can be wasted (become exhausted, in vote counting terminology). A vote for a candidate who has insufficient support to be elected cannot be used to help elect any alternative candidate because no information on further preferences is provided. More subtly, but just as important, a vote for a candidate who has more than enough support to be elected cannot help elect any additional candidates.

Comment 2

If ballots were considered to be formal even though they indicated preferences for a smaller number of candidates than the number of positions to be filled, there would be the possibility of there being no formal votes cast, or extremely few formal votes cast, for one or more of the last positions to be filled in the count, which would be a most undesirable outcome.3

Are exhausted votes a concern?

With fully optional preferential voting, the number of informal votes is at its minimum. If the number of votes exhausting is fewer than the number gained by decreasing the number declared informal then there is a net gain in voter participation.

Votes exhaust when an excluded candidate’s votes are unable to be transferred to another candidate, either because they plumped for one candidate or because all other candidates preferenced have either already been elected or excluded.

In a fully optional preferential STV ballot how many votes fail to give second preferences?

Data is available for the Legislative Assembly elections in the Australian Capital Territory, where voters are allowed to vote for only one candidate and still have their vote counted. Examining the votes of candidates who received over a quota on the first count provides information on how many voters chose this option.

ACT Legislative Assembly – Candidates Receiving Over a Quota

|

Candidate

|

Electorate

|

Year

|

Single No.1s

|

Total Vote

|

% of Total Vote

|

|

Gallagher

|

Molonglo

|

2012

|

124

|

23996

|

0.51

|

|

Seselja

|

Brindabella

|

2012

|

123

|

18566

|

0.66

|

|

Stanhope

|

Ginninderra

|

2008

|

81

|

13461

|

0.60

|

|

Gallagher

|

Molonglo

|

2008

|

118

|

13931

|

0.85

|

|

Seselja

|

Molonglo

|

2008

|

160

|

16739

|

0.95

|

|

Smyth

|

Brindabella

|

2004

|

57

|

12810

|

0.44

|

|

Hargreaves

|

Brindabella

|

2004

|

36

|

10634

|

0.33

|

|

Stanhope

|

Ginninderra

|

2004

|

89

|

21929

|

0.40

|

|

Stefaniak

|

Ginninderra

|

2004

|

48

|

10204

|

0.47

|

|

Stanhope

|

Ginninderra

|

2001

|

38

|

13640

|

0.27

|

|

Humphries

|

Molonglo

|

2001

|

77

|

15856

|

0.48

|

|

Carnell

|

Molonglo

|

1998

|

163

|

25379

|

0.64

|

This is an overall rate of 0.55%. Under any form of compulsory preferencing, every one of these votes would have been informal. Under fully optional preferential voting, none of these votes exhausted. This 0.55% is a net gain in voter participation.

Comment 1 above was also concerned about the transfer of votes from a candidate with over a quota.

More subtly, but just as important, a vote for a candidate who has more than enough support to be elected cannot help elect any additional candidates.

This is wrong and demonstrates a clear and prevalent misunderstanding about how preferences from candidates elected with over a quota are counted.

There would have been virtually no effect on the outcome of the ballot if every one of these single No. 1s in the above table had in fact given further preferences. All that happens is the transfer value changes in the third decimal place. More votes are transferred but at a lower transfer value. The single No. 1s stay with the elected candidate and the surplus is carried by the other votes. Had the potential preferences for the single No. 1s been in the same ratio as the other preferences then the outcome is exactly the same.4 Had the candidate received exactly a quota then no votes are transferred.

ACT Legislative Assembly – Molonglo Candidates Exhausted Votes

|

Candidate

|

Party

|

Vote

|

Exhausting

|

%

|

Candidates in Party

|

|

Biggs

|

Ungrouped

|

464

|

9

|

1.93

|

2

|

|

Jha

|

Lib/Dem

|

536

|

13

|

2.42

|

2

|

|

Pocock

|

Ungrouped

|

816

|

23

|

2.81

|

2

|

|

Gardner

|

Lib/Dem

|

994

|

51

|

2.81

|

2

|

|

Curran

|

AMP

|

1108

|

10

|

0.09

|

2

|

|

Kerlin

|

Greens

|

1285

|

6

|

0.04

|

4

|

|

Gordon

|

Liberal

|

1834

|

8

|

0.04

|

7

|

|

Siddle

|

Greens

|

1846

|

21

|

0.11

|

4

|

|

Matthews

|

Labor

|

1979

|

9

|

0.04

|

7

|

|

Cumbers

|

AMP

|

2141

|

73

|

3.40

|

2

|

|

Drake

|

Labor

|

2634

|

16

|

0.06

|

7

|

|

Dickerson

|

Bullet

|

2726

|

54

|

1.98

|

2

|

|

Kulasingham

|

Labor

|

3272

|

26

|

0.07

|

7

|

|

Milligan

|

Liberal

|

3610

|

152

|

4.21

|

7

|

|

Sefton

|

Liberal

|

5276

|

115

|

2.17

|

7

|

|

Bohm

|

Bullet

|

5464

|

873

|

15.97

|

2

|

If these single No. 1s were declared informal:

- the candidate loses the full value of the vote

- the transfer value of the other votes is reduced

- the candidate may no longer reach a quota and may not be elected

- the quota for the election is reduced

- the voter is disenfranchised.

If a single No. 1 vote is given to a winning candidate or the first runner up, it is included in the tally, being counted at full value to help the candidate to reach a quota. It then never moves and does not exhaust.

In the 2012 Molonglo election, 66% of first preferences were directed to candidates that either won or were the first runner up. Logically this will always be the case; popular candidates receive the most votes. Why should this vote be declared informal when there is only a 34% chance that it would have been distributed anyway?

Information is available to indicate how many votes supporting unpopular candidates actually exhaust. The above table shows the number and percentage of votes that exhausted as each candidate was excluded, in the 2012 ACT Legislative Assembly elections for the seven seat electorate of Molonglo.

After sixteen candidates were excluded and two candidates were elected, the exhausted rate was 1.59%.

Bohm (Bullet Train for Canberra) was the last of the minor party candidates to be excluded. The exhaustion rate for Bohm at 15.97% seems high, but at this point in the count 17 of the 26 candidates had either been elected (2) or excluded (15) and were therefore unavailable to collect preferences. Only the scrutineers could tell us, but it is likely that the majority of these votes would still have exhausted under the more stringent rules of “vote for as many candidates as there are to be elected”, despite having voted in four separate columns.

It is not possible to continue the above table further because of the large number of candidates already elected and excluded. The remaining candidates all belong to Labor, Liberal or Greens (the successful groups) and there is no reason to suppose that the votes received by those candidates would markedly vary from those of their more unsuccessful colleagues in the table above.

Even though these votes exhausted, they are still not totally wasted. They do advise the candidates just how much, or how little, support they actually have and had the electorate as a whole voted differently, they might have counted. As informal votes they can do neither.

If voters are inadvertently letting their vote exhaust, then the only outcome of forcing them to number more candidates than they already have is to convert the exhausted votes into informal votes. Of course, all the votes with similarly inadequate numbering that are currently supporting candidates still in the count will also be declared informal.

If voters are deliberately choosing to let their votes exhaust, it is unlikely that forcing them to vote for more candidates will prevent this.

There are a number of likely outcomes of requiring the compulsory numbering of preferences. Some voters will resent the compulsion and vote informally; some will seek out sufficient makeweight candidates to circumvent the requirements; some will donkey vote from Group A; and some will just randomly number sufficient candidates to comply with the requirements.

It is hard to see how any of these actions will, as required in the quote above, help the “vote counting system…arrive at a good democratic result”.

Increasing the number of compulsory preferences to the number of candidates to be elected (as in comment 2 above) does not eliminate sufficient exhausted votes to overcome the increase in informal votes and the consequent decrease in voter participation. Paradoxically, the exhaustion rate actually increases.

Ballot papers cannot be taken in isolation. Candidates and political parties know the formality rules and to help ensure that their supporters vote formally they will all stand as many candidates as is necessary to ensure a formal vote. Observation of NSW Local Government elections confirms this.

The first consequence is that the number of candidates would increase. The table below provides a comparison between the number of candidates in the ACT 2012 elections and the probably increased number under compulsory preferential voting.

|

Electorate

|

Groups

|

No. of Candidates

|

Probable Increased No.

|

|

Molonglo (7)

|

6 + 2 ungrouped

|

26

|

44

|

|

Brindabella (5)

|

5 + 3 ungrouped

|

20

|

28

|

|

Ginninderra (5)

|

7 + 4 ungrouped

|

28

|

39

|

Increasing the number of candidates to match the formality requirements will increase both the informal vote and the exhaustion rate.

In the 2012 ACT elections, with one exception, only the Labor and Liberal Parties ran a full complement of candidates. The exception was the Marion Le Social Justice Party which ran five candidates in the five member electorate of Ginninderra. They polled poorly and when Marion Le, the last candidate from this group, was excluded early in the count, 217 of her 767 votes (28.2%) exhausted. This exhaustion percentage was greatly in excess of all other candidates. The other four candidates in this group had exhaustion rates between zero and 2.3%.

The reason this percentage was so high is that voters, having been told that they should vote for five candidates, did exactly that. They voted for the five candidates in the group and then, believing they had completed their task, stopped. Being “allowed” to run fewer candidates eliminates makeweight candidates, concentrates the vote for the remaining candidates and encourages voters to explore giving preferences outside their favoured group. This reduces the exhausted vote.

Those who consider that optional preferential voting above-the-line is a sensible model for electoral reform should consider the very high rate of exhausted votes (especially with a half Senate quota of 14.3%) that this would engender.

Perceived Problem No. 2: some candidates may be elected without achieving a quota

A recent comment we received was:

On the other hand, those who argue for full expression of preferences are concerned that optionality leads to exhaustion, and the filling of positions without a full quota.

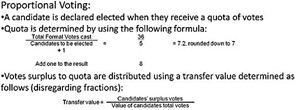

A quota is only a device to ensure a proportional result. It is not a value judgment.

A quota may be described as a percentage but it is only a number. With three to be elected, a quota is one vote more than a quarter of the formal vote; with four to be elected a fifth; with five to be elected a sixth; and so on. As the informal number goes up, so the quota, as a number, goes down.

There are a number of ways to reach a quota: obtaining sufficient votes as first preferences; obtaining sufficient preferences from other candidates’ surpluses; gaining votes as other candidates are excluded; or a combination of surpluses and exclusions, and sometimes with the largest remainder. Once elected, all candidates are equal.

As more votes are included in the count by decreasing the informal rate, the quota, as a number, will increase. However, the quota, as a percentage, will remain the same. While some candidates may be elected with less than a quota, all elected candidates will still have the same or greater number of individual votes.

Conclusion

The single transferable vote (STV) form of proportional representation is a clean, open system that allows voters full freedom to express preferences for individual candidates with or without regard to the candidates’ party affiliations. It also enables the elected body to reflect, within limits of a few percent, the strength of political parties or other groups of opinion among the voters.

Votes do not belong to politicians or party directors, candidates or general secretaries – they belong to the voter. No one has the right to say to voters “although you have made a clear unequivocal choice we will not count your vote”.

We do not recommend that voters only vote a single No. 1 and we do believe that electoral commissions should encourage voters to give preferences for as many candidates as they feel able. They should also publicise the fact that later preferences can never harm the prospects of candidates supported with earlier preferences.

To restore trust in our electoral system, we have to trust the voters and give them back control of their own preferences. We do this by abolishing above-the-line voting and associated group voting tickets and implementing fully optional preferential voting.

1� Enid Lakeman, How Democracies Vote (London, 4th ed., 1970) at 14.

2� Michael Maley, ‘Optional Preferential Voting For The Australian Senate’ (Working Paper No. 16, Electoral Regulation Research Network, November 2013) at 18-19.

3� The author can find no example in any jurisdiction using fully optional preferential voting such as the ACT, Malta, or Ireland or even large community organisations such as the Australian Conservation Foundation, where such a situation actually occurred.

4� Don’t believe the nonsense that if too many votes fail to give preferences, the transfer value will rise above 1 and votes will be lost. For this to happen, over a quota of the candidate’s votes would have to be single No. 1s. In Molonglo this number would be 11442 – a long way from 124. Many more ridiculous scenarios would occur before this one did.